The Mystery of Black Madonnas

By Ella Rozett

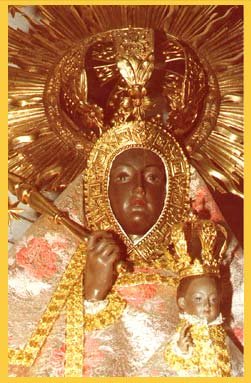

Our Lady of Good Deliverance, in Paris

To many Christians Mary is the Heavenly Mother of all; and like a good mother she seeks to meet all the needs of her children. Especially as the mysterious "Black Madonna" she allows people to project their hopes, desires, and needs unto her, as she draws them ever deeper into divine mysteries.

She plays many roles for many different kinds of people: She is the heiress to the thrones of the pre-Christian goddesses, many of whom were black. She is the bride of the Christian God, the bride in the Song of Songs, who represents all souls seeking intimate union with the Divine and says: "I am black and beautiful." (1:5, in the original Hebrew, often translated as “black but beautiful”) She is a rebel against the establishment, a heavenly therapist, a spiritual guide. As a black woman she is the mother of the oppressed, exploited, silenced, marginalized, and the reconciler of all races. She is a healer of all dis-ease, a guide and companion at the time of death. As the Dark Mother archetype she is a symbol of our inner shadow-self when properly integrated. She is the co-redemptrix with Christ, carrying and transmuting our sins with him. This idea is sometimes expressed in images showing Mary almost crucified with her son, like in the mosaic in the church of the Black Madonna of Vichy. I see Mark Doox expressing a similar idea in his icon of Our Lady of Ferguson, which shows Mary and Jesus taking the bullet for their oppressed and persecuted children, saying: “Whatever you do to the least of our children, you do to us!”

For centuries, Catholics honored Black Madonnas as expressions of Mary carrying the sin and pain of her children. And yes, sadly, there has been a racist element in using darkness as a way of portraying negativity and that racism goes back to pre-Christian times, when the bride of the Song of Songs was shamed for being black. Happily she was able to affirm: “I am black and beautiful!” All devotees of the Black Madonna agree with her whole heartedly: “You are black and beautiful!”

photo: detail of original by John Malathronas

TABLE OF CONTENT

Mother Earth, Pagan Goddesses, and Black Madonnas

The Church's explanations for Black Madonnas

Christian and non-Christian Feminist views

Is the Mother of God Christian?

Our Lady of the Good Death: the Dark Mother as Guide through the Underworld

Other symbols of Mother Mary's divinity

Black Madonna Themes

Other subjects are embedded in posts on individual Black Madonnas in my index, sorted here by key words. Some of these topics are elucidated in detail, others are just recurrent themes - Black Madonna leitmotifs.

Black Madonna Bathing: Les-Saints-Maries-de-la-mer, Thuir

Black Madonnas and Bees: Duesseldorf

Black Madonnas breast feeding their devotees (Maria lactans): Chatillion-sur-Seine

Black Madonnas, Sacred Bulls and other Cattle: Olot, La-Chapelle-Geneste, Prats-de-Mollo, Foggia, Milicia, Monte Civita, Vena, Naga City, Guadalupe de Carceres, Nuria, Lord, Santisteban-del-Puerto (12)

Black Madonnas and Childbirth Rituals: Toulouse, Nuria, Marsat, Thuir

Black Madonnas Crowned or consecrated by Angels: Foggia, Le Puy, Einsiedeln

Black Madonnas imported from the Middle East by Crusaders: Aurillac, Liesse-Notre-Dame, Mende, Molompize, Moulins, St-Guiraud, Huy (7)

Black Madonnas associated with a Good Death: Clermont-Ferrand, Mont-Saint-Michel

Black Madonnas and Dragons: Ronzieres

Black Madonnas with title ‘the Egyptian’ or the ‘African’: Meymac, Le Puy, Vernazza, Luxembourg

Black Madonnas and the goddess Kali: Les-Saints-Maries-de-la-mer, Siparia

Black Madonnas ‘made without (human) hands’ (acheiropoieta): Las Lajas, Mexico City, Zaragosa

Black Madonnas and Mary Magdalene: Marseille and “Mother Mary and Mary Magdalene”

Black Madonnas and Menstrual Blood: London

Black Madonnas with Nigra Sum Sed Fermosa inscriptions: Tindari, Prague, Marseille, Lluc

Black Madonnas Self-determining their place of worship: Penrhys, Czestochova, Cusset, Oropa, Juquila, Cardigan, Cusset, Dorres, Orcival, Costa Rica, Cuba, Walcourt, Huy, Tindari, Milicia, Positano, Tindari, Lloseta, Lluc, Montserrat, Nuria (21)

Black Madonnas and Sexuality: Montevergine, Solsona

Black Madonnas attributed to St. Luke the Evangelist: Andujar, Bologna, Brno, Crotone, Cyprus, Czestochova, Guadalupe de Carceres, Madrid, Manfredonia, Marseille, Monte Civita, Montevergine, Montserrat, Naples, Orcival, Oropa, Piazza Armerina, Turin, Venice (19)

Black Madonnas and Sacred Stones: Le Puy, Arconsat, Mauriac, Costa Rica

Black Madonnas and Trees: Altoetting, Antipolo, Bar-sur-Seine, Caversham, Err, Foggia, Halle, Handel Meerveldhoven, Monte Civita, Neuerburg, Oirschot, Penrhys, Swieta Likpa/Heiligenlinde, Telgte, Walcourt, Willesden,(18)

Black Madonnas with Sacred Wells or Springs: Caversham, Penrhys, Liesse-Notre-Dame, Marsat, Arconsat, Chartres, Dorres, Egliseneuve, Font-Romeu, Orcival, Ronzieres, Sankt Veit, Vassiviere, Vichy, New York, Costa Rica, Heiligenbrunn (17)

Black Madonnas and Wheat: Custonaci, San Severo

Whitened Black Madonnas: Chartres, Chatillon-sur-Seine, Cuxa, Err, Font-Romeu, Molompize, Prats-de-Mollo, Ronzière, Magdeburg, Custonaci, Milicia, Padua, Pescasseroli, Piazza Armerina, Nuria, Olot, Serralunga di Crea (16)

Black Madonnas with white baby Jesus or ‘Yin Yang Madonnas’: Foggia, Chipiona, San Severo, Santisteban-del-Puerto

Definition

What exactly are Black Madonnas? Good question! Some are images of Mary the Mother of Jesus that portray her with pitch black skin, while her garments are colorful. Others are entirely made of a blackened metal or wood. Yet others simply darkened with patina, the normal aging process that all antique art and furniture undergoes. But - while countless very old statues are dark, only some of them have been honored with the special title "Black Madonna", "Black Virgin" or "Black Mother of God".

This title is a Catholic invention, unknown in Orthodox and Protestant Churches, except in the Anglican Church. Even on the rare occasion that Orthodox Christians revere a Catholic Black Madonna, they give her a different title. E.g. Our Lady of Loreto is known in the Russian Orthodox Church as ‘Increase of Reason’ because she is invoked especially to help with mental strength. See: “A Reasonable Look at the ‘Increase of Reason Icon’”

Traditionally, a real Black Madonna is not something one can just produce; it is something that happens to a community when Heaven ordains it to be so. Countless wonderful legends tell of the sacred or miraculous origins of these images. More than thirty are said to have been created by Luke the Evangelist, others were presented to humans by angels or the Virgin Mary herself; many were found when simple people or even cattle, guided by divine forces, uncovered statues hidden in the earth, in caves, springs, or trees.

To me, the question is not whether these legends with their recurring themes are “real” or not. Since I believe in miracles I think some are and some aren’t, but even if a legend is completely made up, it’s important to look at the message it puts in Mary’s mouth. What are her children expressing with her help and, I think, with her consent?

More research must be done to establish how the process of giving a dark statue the official title of "Black Madonna" worked over the centuries, but it seems to be a grass roots kind of movement. I think, just as in the Catholic Church the faithful usually acclaim a holy person as a saint long before the Church gives its official stamp of approval, so also certain, usually miraculous, dark Madonnas are hailed as Black, first by the simple people and then by the entire church.

Once a community has been given the divine privilege of a Black Madonna, they don't usually let go of her. If she is destroyed, they replace her, giving the new statue the same name and title and attributing to her the same miraculous powers. Even if she is whitened in a misguided effort to restore her to her original state, the people often continue to call her Black.

The only way for a community to come by a Black Madonna when Heaven has not bestowed that gift, is to make a so-called "copy" of one of the famous Dark Mothers. Often these works are variations on a theme rather than copies. They seem to be labeled as copies because they need the original to grant spiritual power and a justification for creating a Black Madonna. Sometimes they are even sent to spend some time with the original statue, in order to be imbued with its spiritual power. For example the Black Madonna of Rumburk, Czech Republic, a copy of Our Lady of Loreto, spent one week in the Holy House of Loreto (see below) imbibing the grace and identity of her mother statue. Other copies, like the Black Madonna of Riegelsberg, are touched three times to the original, clothed in her mantle and regalia, and have relics associated with the original inserted into them.

Our Dear Lady of Altoetting, the original (left) and a "copy" on the Women's Island in Lake Chiem (Fraueninsel im Chiemsee), both in Bavaria, Germany

Characteristics of Black Virgins

The big question is, why do the people want a Black Mother figure? Before answering it, let's look at some of the characteristics of Black Madonnas.

French scholars tend to define only one type of dark Madonna as "authentically black": the first Black Virgins (as the French call them) in Western Europe, who were conceived as pitch black from the beginning. According to Jacques Huynen they share thirteen characteristics.[1]

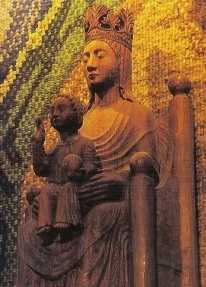

1) They are of Romanesque style, sculpted in wood in the 12th and 13th centuries. As far as we know no French Black Madonnas were sculpted until the 1100's and none were mentioned in literature until the 1500's.

Romanesque Madonna of Chastreix, Puy-de-Dome, France Photo: Francis Debaisieux

2) They are portrayed in the position called "majesty" or "Seat of Wisdom". That is to say, Mary sits on a throne with a low back; she holds a toddler Jesus on her knees; both look straight ahead - no demurely down cast eyes. In the language of medieval symbolism this means that Mary is the throne of Jesus, the Seat of Wisdom. From her lap spring wisdom and power. She is represented as the Christian embodiment of Lady Wisdom, a personage described in the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament) as the first companion or the feminine face of God, through whom he draws people to himself. Much of what the Old Testament says about Wisdom is later attributed to the Holy Spirit and to Christ. Here are some excerpts from the Book of Wisdom, chapters 7-9:

"Such things as are hidden I learned and such as are plain; for Wisdom, the artificer of all, taught me. For in her is a spirit intelligent, holy, unique " all-powerful, all-seeing, and pervading all spirits. " she penetrates and pervades all things by reason of her purity. For she is an aura of the might of God and a pure effusion of the glory of the Almighty; she is the refulgence of eternal light, the spotless mirror of the power of God, the image of his goodness. And she, who is one, can do all things. And passing into holy souls from age to age, she produces friends of God and prophets. Indeed she reaches from end to end mightily and governs all things well. "Now with you [God] is Wisdom, who knows your works and was present when you made the world;"

Seat of Wisdom was also one of the titles of the Egyptian goddess Isis, like Mary, often portrayed with her son Horus on her lap. Mary shares many other goddess titles, like Queen of Heaven, Star of the Sea, Morning Star, etc. One of her most interesting titles, reminiscent of her identification with Lady Wisdom, the feminine face of God, is Adonai, which is Hebrew for Lord God. There is a dark 3rd century fresco of the Madonna with child in Brucoli, Sicily known as Madonna Adonai, Saint Mary Adonai, Most Holy Mother Adonai, or simply Adonai.[2]

3) Their facial expressions are not tender and compassionate like those of later Marian images, but nobly aloof and sovereign. They portray a heavenly majesty far beyond our human realm of suffering.

4) Huyen finds that more care was given to the traits of the mother than the child. I disagree.

5) The colors of their robes were originally white, red, and blue with golden fringes, though they may have been changed during renovations.

These colors were important in alchemy, an ancient discipline practiced in all the great civilizations. It sought transforming knowledge. The goal was to transform lead into gold, disease into perfect health, ignorance into wisdom, and humans into God. (Remember that the Catechism of the Catholic Church still lists the "divinization of man as Jesus' goal".)[3]

Black Madonnas were the symbol for that latter goal, pursued in the Great Work (opus magnum), which had three phases:

I. The Blackening, or the Black Sun (nigredo, sol niger). This is where all the impurities of the primal matter (the ordinary human) are burned and it turns black. This blackness stands for the death and rotting of the old false self. On Black Madonnas it is represented not only by her black skin, but also by the dark blue of her robes - dark blue as the night sky.

II. The Whitening (albedo) is the phase where the soul becomes spiritualized and enlightened.

III. The Reddening (rubedo) is the color of the "secret fire" that unites human and divine, the limited with the unlimited.

Having passed through these three stages, lead would turn into gold and a human into God. Mother Mary, as the prime human soul to have undergone this transformation, is adorned with golden fringes and jewelry. Hence a Black Madonna dressed in dark blue, red, and white, and decorated with gold, portrays the whole process of spiritual evolution.[4]

6) The originals usually measured 70 centimeters in height, 30 cm in width, and 30 cm in depth, with slight deviations resulting from differing heights of the pedestals and hair dresses. This 7:3 proportion echoes sacred numerology that goes back to pre-Christian times. In the Christian context it speaks of the union of God (the 3 persons of the trinity) and his creation (made in 7 days). No other Christian statues shared such a rule concerning their dimensions. Romanesque depictions of Christ and other saints came in all different sizes. Hence the Queen of Heaven with her 7:3 ratio may embody the divine and its creation.

7) They were enshrined at places that were sacred even before Christianity, pagan holy sites and natural "power spots" of exchange between heaven and earth.

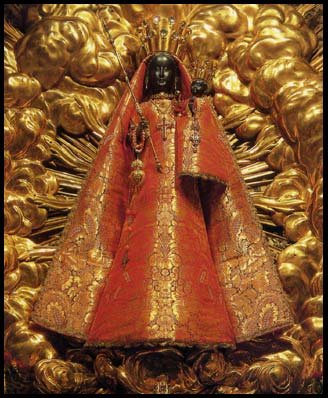

A prime example is Our Lady of Oropa. Tradition recounts that St. Eusebius (martyred in 371 A.D.), led by divine inspiration, found this statue in Jerusalem, buried under ancient ruins. He brought her to Italy and installed her in a cave that was a pre-Christian holy site, in order to end the local, pagan practices. The woods around it were consecrated to Apollo and the large rocks to various goddesses. Apparently Our Lady became quite attached to this sacred place. When a group of monks tried to move her to a new location, more than a thousand years later, she refused to go. She allowed them to move her half a mile and then the three foot tall wooden statue became so heavy that no one could budge her until they decided to return her to her cave.

It is believed that Luke the Evangelist carved this statue. She has worked so many miracles and became so important to the Italians that four Popes crowned her. Hence the 3 crowns and the halo with diamond studded stars.[5]

The Black Madonna of Oropa, Italy

8) They all have some connection to the Near Eastern Orient, i.e. the Holy Land or its neighbors, like Egypt, Syria, Ethiopia, etc. Many are said to have been sculpted or painted by Luke or else been brought to Western Europe by a crusader, preferably of royal descent.

Most of these claims seem to have been invented as a way to legitimize and protect the images from the recurring attempts to enforce the commandment: "Thou shall not make any image or any likeness of anything..."

The feeling was that if these statues and icons came from the cradle of Christianity and if some had a direct link to the disciples of Jesus (even if they called to mind Pagan images), then surely God must have revoked his Old Testament prohibition against images.

Our Lady of Czestochowa, Poland, said to have been painted by St. Luke the Evangelist

9) They became favored places of pilgrimage. Many were famous stopping points on the way to Santiago de Compostella or else they constituted alternative destinations for those who could not make it as far as Spain.

10) Their shrines all have a connection with either the Benedictines, the Cistercians, or the Knights Templars. All three of these orders were strongly influenced by St. Bernard (1090-1153), the man who was instrumental in establishing a widespread and fervent popular cult of Mary. He had a very special relationship to his own Black Madonna. (See Chatillion-sur-Seine for details.)

11) Symbols of esoteric initiation were to be found in their sanctuaries. Where these have been destroyed related clues hide in the legends describing how they came to France. "Esoteric initiation" denotes all the teachings and practices that were meant to lead to divine knowledge, mystical union, or the direct vision of God. Once the soul was purified to where it could see God, this supreme enlightenment would make it able to grasp all kinds of knowledge and handle it in a responsible way. Medieval consciousness did not separate mystical, scientific, philosophical, and artistic knowledge. It all came from God and was to lead back to him.[6]

12) They are seen as particularly powerful, i.e. miraculous. They manifest this miraculous power in the way of their apparition and/or in their granting of graces.

13) Unusual rituals that Catholic tradition can no longer explain are offered to them. E.g. burning a wheel of fire as an offering before them, or washing them with wine, or carrying them in procession to a stone outside the church, or offering them green candles.

There are less than 50 of these early Black Madonnas.

American scholars don't have clear criteria for what constitues a Black Madonna. They simply acknowledge all who are claimed as such, at least 450 world wide, still counting. I think there are many more. In 1991 Miquel Ballbè i Boada published 2 volumes entitled "Las Vírgenes Negras y Morenas en España"[7] in a limited edition. He lists 225 in Spain alone.

Black Madonnas have been reported in: Belgium, Brazil, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Ecuador, England, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Malta, Mexico, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Switzerland, USA, etc. The list keeps expanding as more people research the phenomenon. (For an extensive list of statues see www.udayton.edu) They come in different positions, seated or standing, with or without baby Jesus. They can be as "young" as from the 16th century and they come in all shades of brown and black.

Our Lady of Montserrat, Spain, said to have some connection to Jerusalem and James, the brother of Jesus.[8]

Some Black Madonnas clearly reveal the artist's intention to portray a pitch-black mother and child: the faces and hands of both are painted black, while the clothes are brightly colored. With others it is not at all clear whether someone wanted to craft a "Black Madonna". Often it seems that the faithful proclaimed her "black" quite independent of the artist's intentions. Some are Byzantine icons whose complexion is usually dark, approximately in accordance with the actual skin color of Palestinian Jews of the 1st century. Some statues are dark because they are sculpted out of dark wood or cast in a dark metal; skin and clothes are all the same color, though the statues are often draped in bright cloth clothes, which accentuates the darkness of the material.

The Virgin of Guadalupe is hardly dark at all, though the painting's colors may have faded over the centuries. The Mexicans call her La Morenita (the dear dark one) not so much because of her color in this miraculous painting, but because of her color in the story behind the painting. Mother Mary appeared to Juan Diego in the form and dress of a dark Aztec princess, saying: "Am I not one of you?!" But then she gave him a self-portrait of who she was to become: a mix of Aztec and Spanish Heavenly Mother and the mother of her mixed blooded Mexican children.

The Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe and the Spanish Virgin of Guadalupe de Caceres, after whom her Mexican sister was named.

The latter is Patronness of Extremadura and of all that is Hispanic. Photo: Jose Corrales Guisado from www.mercaba.org

Many more Black Madonnas were created but destroyed during religious wars, or are kept from the public eye in private property. Some were ordered to be whitened by church officials, supposedly in an effort to "beautify" them. But the people, the faithful, are undeterred; they still call them black.

I would count every Madonna as black that has been given that title by her devotees, no matter what color she is or why she is dark, because the fundamental question is: Why do people want and need to regard some Madonnas as black? What is this spiritual, psychological, and political need for a black mother? To answer this question, we have to look into the religious history of Europe.

Mother Earth, Pagan Goddesses, and Black Madonnas

Most Black Madonnnas have a strong connection to the earth. They are found buried in it (see Guadalupe de Caceres) or appear in trees (see Telgte), caves (see Montserrat), springs (see Font-Romeu), on mountain tops (see Dorres), by a sacred rock (see Le-Puy), and in the jungle (see Costa Rica). Often they are found with the help of animals guiding the way (see Olot). And so Pagan worship of Mother Earth turned into a Christian closeness to God’s sacred creation, mother nature.

One may wonder: as the Church appropriated Pagan objects of worship like trees, groves, springs, and rocks, did it value their sacredness or was it merely a ploy so that they could be controlled and gradually erased from people’s consciousness? I think both. “The Church” is not a monolith. There were clergymen who had no respect for anything Pagan, natural, or feminine. But there were also mystics who saw the divine in everything around them, and there were (and are) many who were both privately mystical, but publicly power brokers and politicians.

Saint Ambrose (4th century), one of the most influential Church Fathers, likened Mary to the earth when he said, ‘as Adam came from the virgin earth, so Christ came out of the Virgin Mary’. (“ex terra virgine Adam, Christus ex virgine.”) In the monastic rule of St. Benedict (480 – 547 A.D.), a direct link is made between our relationship to the earth and to God. It says: “Humans must cultivate the earth if they want to cultivate God.”[9] Later, St. Francis (1181/1182 – 1226 A.D.) would sing of his love for the earth, which was inseparable from his love for God.

Most of the time the Church was in no hurry to do away with sacred springs, trees, and rocks, though intermittently some did worry about them being “un-Christian”. For example, Emperor Charlemagne wrote in a letter in 789 A.D. “Concerning the trees, stones, and springs next to which some poor souls light torches or practice other rites, we order that these customs, which are loathsome to God, shall be completely annihilated and shall disappear everywhere.”[10] But then the Virgin Mary, the Queen of Heaven, came to the rescue of sanctified nature, saying: “On the contrary! Build me a Christian church around this sacred stone (e.g. in Le-Puy) and next to this healing well (e.g. in Vassivière).” And she appeared in a tree, making it holy (e.g. in Foggia) and guided cattle to finding her in the earth (e.g. in Lord).

In order to be able to keep venerating the same ancient trees, springs, and rocks that were consecrated to Pagan deities, Christians merely had to consecrate them to Christian saints. Many were baptized, so to say, in the name of Mary. Why her instead of Jesus? Because the feminine was always seen as more connected to nature and the earth: mother earth and father sky.

So Mary came to represent the earth and all of the “new creation”, all that was redeemed since she had said yes to receiving God into her womb. As Stephen Benko says: “In this hieros gamos [holy wedding] Mary received the role of the bride, as the “virgin earth” who was impregnated by the word of God, as the symbol of the Church, the bride of Christ, and as Queen of Heaven.”[11]

For centuries there was a measure of peaceful mingling of nature and Christian worship. Things got precarious again with the 16th century Reformation and the following “Enlightenment” or “Age of Reason”. In that era much of Catholic tradition, with its ancient, pre-Christian roots, became ridiculed as superstition and tossed out.

While some Catholics find it somehow "heretical" to speak of the pre-Christian roots of devotion to Mother Mary, many, especially European clergymen have no problem with this at all. For centuries the Church was very clear that it meant to establish itself on the foundations of its "pagan" predecessors, like grafting a new shoot onto an old trunk. Christians knew they needed those old roots and celebrated them. E.g. both in Rome and in Assisi you will find a church called Santa Maria Sopre Minerva, St. Mary on top of (the goddess) Minerva. All over the Roman empire temples were converted to churches, churches were built on top of "pagan" foundations, and wherever possible, goddess images were converted into madonnas.

Without any embarrassment a German priest writes about the origins of Black Madonnas: "In the parts of North-Africa that were influenced by Egypt, representations of Black Madonnas apparently have a special tradition. Coptic [i.e. Egyptian] and Ethiopian Christians reinterpreted the common and black images of Ceres [=Demeter], the goddess of fecundity, and of Isis with her young son Horus as the Mother of God and baby Jesus."[12]

Now, some of the most important Pre-Christian goddesses who were worshipped side by side with Christ, overtly until the 6th century, covertly until the 11th, are associated with the color black. Why? Going back to prehistoric times, black was the symbol for the earth and the Great Mother, the source of heaven and earth. The darker earth is, the more fertile, hence black is the color of fertility and creative power. But the ancient peoples knew that that which has power to create and to bring forth life also has power to destroy. ("The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh; blessed be the name of the Lord.", says the Bible in Job 1:21.) Hence black also became the color of death and destruction. So, the Great dark Mother became known as "the Gate of Life" which opens both ways, to life on earth and to death, or life in the Goddess after physical death.

Echoing that title of the goddess, Mary is called the "Gate of Heaven" (e.g. in the Litany of Loreto). She too is a door that opens to the worlds below and above, because divine life and salvation in the form of Jesus Christ came to our world through her and we in turn can enter Heaven through her.

the goddess Artemis of Ephesus with her many breasts or balls?! For the answer see Black Madonna of Montevergine or Alessandra Belloni’s “Healing Journeys with the Black Madonna” pp. 110-13

ARTEMIS of EPHESUS was one of the most powerful goddesses of antiquity. She was a classic black Universal Mother and was older, more powerful, and more primal than her later Greek forms and her Roman equivalent Diana. Her temple was one of the Seven Wonders of the World and the largest building in the world to have been constructed entirely of marble. Her presence inundated the atmosphere of Ephesus, providentially also the city where Mary lived after the crucifixion of Jesus.[13] It does not seem a coincidence at all that it was here that the Council of Ephesus in A.D. 431 proclaimed Mary "Mother of God". Perhaps a divine plan brought the Virgin Mary and one of the most revered goddesses of her time together in one place for a purpose.

CYBELE arose not far from Artemis, as the Phrygian form of the "Great Mother of the Gods" and as another one of the oldest goddesses of Asia Minor. Her worship reaches back at least to the Neolithic period of the Stone Age. This seems fitting because she was represented by a stone, a black meteor.

Peter Lindegger links Cybele to Ishtar, the Sumerian-Babylonian Queen of Heaven, whom the Israelites worshipped as Asherah (much to the chagrin of Biblical prophets).[14] In the form of Cybele this goddess becomes more closely linked to death and the underworld and is portrayed with a black face.

Cybele's city, which the Greeks called Metropolis, i.e. the city of the Mother, was in Anatolia, now part of Turkey. This Mother of all Gods was also regarded as a virgin. That is to say she was able to give birth without intercourse with a male counterpart, and when she did have intercourse her virginity was always restored afterwards.

There appears to be a connection between Cybele, also known as Kubaba, Kube, Kuba, and the central holy shrine of the Muslims, the Kaaba in Mecca, a huge, dark grey cube, covered with a black brocade cloth. Its main treasure is another black meteor, which was already worshipped long before Muhammed, when the Kaaba was the shrine of the Arabian moon goddess Al’Uzza, one aspect of the Triple Goddess known as Al’Lat.[15] Every pilgrim who can, kisses the meteor for the forgiveness of sins. If the crowd of pilgrims is too thick to get to it, one greets it from afar. Like the Black Madonnas, the stone is said to have turned black by absorbing the sins of the faithful. A Muslim told me that it is also considered a person of sorts. Tradition has it that on Judgement Day the stone will come alive and greet everyone who greeted it, thereby allowing passage into paradise — a faint memory of their ancient goddess?!

When Rome was lacking a powerful mother goddess, Cybele was brought there and hence her influence spread in the Roman Empire. Not in Asia Minor but in Greece and Rome, Cybele ruled (like the Virgin Mary) with her son, the god Attis, who (like Jesus) died and resurrected.

During the council of Ephesus in 431 C.E. the Virgin Mary inherited not only the title Mother of God from pre-Christian goddesses, but also all the sanctuaries of Cybele and Isis that had been closed by Roman-Christian edict.

Several Black Madonnas in France have links to Cybele. E.g. the legend of Our Lady of Miracles in Mauriac, France recounts the following events: In the year 507 A.D. a Merovingian princess witnessed from afar a gathering around a dolmen, i.e. a stone sacred to the pagans. By the time she arrived on the scene all that was left was a statue guarded by two stone lions. Since Cybele was normally portrayed with two lions, the message was clear: In those changing times Cybele and other goddesses were going to be replaced by Mary the Mother of God and the sacred stones of the goddess were going to become sacred statues of the Queen of Heaven.

Another example of Cybele's influence is the black, volcanic "fever stone" venerated to this day in the Cathedral of the Black Virgin in Le-Puy-en-Velay, France. It is known to be linked to the pre-Christian era and is said to have miraculous healing powers. Legend has it that the Virgin Mary herself insisted on the sanctuary being built around the holy stone.

"Cybele, Philosophy" , Notre-Dame of Paris

By the Middle Ages ‘Cybele’ had become just another name for the divine feminine, our Lady Wisdom of the Bible, or Lady Philosophy of French alchemists. Below is a 12-13th century relief called “Cybele, philosophy” which is on the West portal of Notre-Dame of Paris. This Lady Wisdom, Cybele, has her feet on the earth and her head in the clouds. She holds two books, one open and one closed, symbols for exoteric and esoteric knowledge, or wisdom gained from books and from interior prayer or meditation. Leaning on her is “Jacob’s ladder”, which represents the gradual way of knowledge of God leading to her scepter of wisdom, divine union.

DEMETER and PERSEPHONE: The Greco-Roman goddess Demeter was known by at least 46 names and titles throughout the Roman Empire: Ceres (from which comes the word cereal), the African, and the Black One are only three of them.

She was the goddess who taught humans about agriculture, especially how to grow grains and make bread, but she also became Tesmofora, the legislator who gave her people wise laws. As Dionysius was the god of wine, she was the goddess of bread. To this day on certain holidays, Sicilian women decorate some villages with bread sculptures and sometimes they openly make the connection to Demeter, the bread goddess.[16] The type of Madonna called Madonna in the wheat-dress also goes back to the bread goddess Demeter. For more see Custonaci.

Demeter is always thought of in conjunction with her daughter Persephone, (also known as Proserpina or Kore (the maiden), who was kidnapped by Hades, the prince of the underworld. The distraught mother Demeter searched for her daughter in heaven and on earth for one or two years. Finally she was able to strike a deal with the captor: half the year Persephone would be with her mother on earth and the world would rejoice with spring and summer; half the year she would dwell in the underworld, bringing sadness, fall, and winter to the earth.

Tying the changes of seasons to this myth firmly entrenched the theme of the divine mother grieving the loss of her divine child all over the Roman Empire. It finds expression to this day in representations of Mary as the mater dolorosa or the pieta, i.e. Mary with seven sorrows (swords) piercing her heart or Mary holding her dead son on her lap. As Demeter was imagined covered in a black veil of mourning, especially by the Sicilians, so the grieving Mother of Christ is often portrayed in a great black cape.[17]

A German professor of theology once explained to me why God has to be a trinity: It’s because in order for God to be everything, God has to be one thing, its opposite, and that which transcends the thing and its opposite. According to Brigitte Romankiewicz, Demeter and her daughter form just such a trinity in that the mother gives rise to the innocent, “white face” of her virgin daughter called Kore, maiden. Then the white maiden becomes the wife of Hades, the Queen of the underworld and puts on the “black face” of death. The one divine womb brings forth light and darkness, life and death, summer joys and winter sorrows, union and separation.[18] The Black face of the Madonna also becomes the guide in the underworld (see below).

CELTIC GODDESSES: Most people think of the Celts as the inhabitants of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and the Bretagne province of France. Actually, between the 6th and 3rd centuries B.C.E. they settled all over Central Europe, as far south as Italy and Spain and as far East as Phrygia (in modern Turkey), home of the Goddess Cybele. They traded goods (which always meant also ideas) with the Greeks.

Like many ancient gods, Celtic goddesses were holistic, all-encompassing; i.e. they had a light and a dark side. They were heaven and earth, summer and winter, illness and healing, life and death, love and war, creativity and utter destruction, beautiful young maiden and ugly old hag, womb and tomb. In each of these activities they were given a separate name. To what extent one saw all these names as faces of the same goddess or as separate entities was up to the tribe, clan, or individual. (The Celts were decidedly not interested in centralized authority, institutions, or dogmas.)

One of the oldest names of the earth-mother goddess of Ireland is Cailleach, the "Veiled One" (reminiscent of the "Hidden God"). Her roots go back to a time before even the Celts arrived in Ireland.

Not only New Age feminists but also the good old 1969 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, citing research from the 30's and 40's in the article on "Celtic Mythology" makes the connection between Cailleach and Kali, the black Hindu goddess of death and destruction: "The great mother" magic horse, represented as having one leg and being impaled on a chariot pole, suggests links with the Scythians to the North of the Black sea, while many of her characteristics are so like those of the Hindu goddess Kali that, coupled with the known survival of hippogamy (mythological creatures that are part horse) in Donegal in the middle ages, it seems probable that these Irish stories belong to a religion which spread from some unknown source both westward and to the Southeast, perhaps 3,000 years ago. What lies half way between the British Isles and India? Iraq, perhaps the cradle of our civilization, perhaps the land of the"Garden Eden" described in the Bible, and now the place the USA has brought so much destruction to!

Supporting evidence of Kali's possible influence on the Celts is also found in the old name for Scotland, "Caledonia", which could be rendered as "land of Kali".

And then Kali brings us back to France, the land of plenty when it comes to Black Madonnas. There is a statue of a Black woman in the crypt of a church in St-Maries-de-la-Mer, whom the Roma venerate as their patron and queen. (Roma is the term used by the EANR, the European anti racism network, for the groups formerly called “Gypsies”.) Her name is Sara la Kali. In Sanskrit, other Indian languages, and according to Huynen also in the language of the Roma, who originally came from India, Kali means ‘black’. So her name could be translated as ' Sara the Black One', though of course in the religious context, leaving it untranslated invokes the Indian goddess.[19]

Perhaps for the purpose of appeasing the Catholic Church (The Roma couldn't very well say: "By the way, we're keeping our goddess of death and destruction in your basement!"), Sara la Kali was hidden inside another story of the divine feminine: that of St. Sarah, the Egyptian hand maid of Mary Magdalene and two other Marys mentioned in the Bible, coming to France after Jesus' ascension into Heaven and carrying with them the Holy Grail. (See: Saint Sarah in www.en.wikipedia.org)

In 2006 I prayed and meditated at the feet of Sara la Kali, asking her: "Who are you?" The response was a somewhat angry insistence: "I will not answer that question!" Then I realized that the black feminine at the heart of the white Church holds the place of unlabeled mystery, a space that is meant to remain free of any concepts, free of arrogant claims like: "I know the absolute truth about her and you'd better listen to me!"

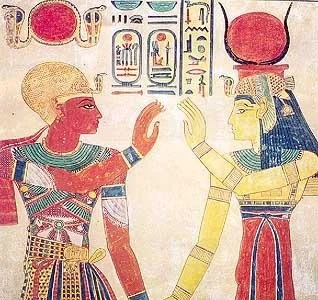

ISIS is often described as a black goddess in feminist and new age literature. Yet in ancient Egypt she was far more often depicted as pale, gold, red or blue. Like the goddesses described above, she did however have a dark aspect: the mourning widow and destroyer. Only this face of her would be represented as black in paintings.

It is true that Isis became one of the favorite goddesses of Romans and that the Virgin Mary came to inherit many of her characteristics. All over the Roman Empire there were Isis statues that were baptized and renamed as images of Mary, Mother of God. Ean Begg mentions one that was venerated in Paris as late as A.D. 1514, when some zealot destroyed her flimsily dressed form.[20] People also venerate little Isis statues in their homes. These were often made of bronze, which over time turns a dark brown, almost black.

It is conceivable that Northern Europeans imagined the Egyptian goddess as black since she was after all North-African. What color were the ancient Egyptians, before they were invaded by Arab Muslims? The Collector, an online magazine on ancient history, philosophy, art, and artists, published a wonderful article entitled “Were Ancient Egyptians Black? Let’s Look at the Evidence”. It states: “… ancient Egypt was always ethnically diverse, so could not be classed as belonging to any one racial category. But it is worth noting that the skin-colour distinctions we have today didn’t exist in ancient Egypt. Instead, they simply classified themselves by the regions where they lived. Scholarly research suggests there were many different skin colours across Egypt, including what we now call white, brown and black.”

For centuries ancient Egypt was the most tolerant and egalitarian culture around the Mediterranean Sea. And so, it is not surprising that its pantheon would include gods with all kinds of features, everything from pale European to dark African. Juliana Rasnic, in her article on Isis and Nut explains that Isis herself was most often portrayed with yellow or golden skin, since the gods were believed to have gold colored skin. But she was also shown with blue skin.

Just as Isis had many faces, colors, and functions (from giving life to destroying, and everything in between) so Mary too fulfills many roles in many ways and with many images. Her not being limited to one sole expression is an essential part of being a heavenly mother. So, one should not fall into reverse racism by accepting only Black Madonnas as "politically correct" and of any interest or by refusing to see Isis' pale faces. As described below, White Madonnas too reveal plenty of goddess characteristics. Undoubtedly Mary, in all her colors, became the heiress to the thrones of all the goddesses.

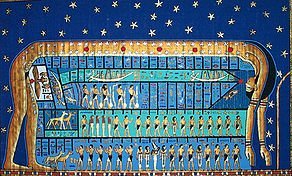

NUIT, also known as Nut, is not a very popular Egyptian goddess, but in a way she is the quintessential divine Dark Mother. She is the goddess of the night and the sky, infinite outer space. The Greeks adopted her as Nyx, the Phoenicians knew her as Baaut, the Peloponnesians as Achlys, the Scandinavians as Nor, and the Polynesians as Po.[21] The Egyptian Nuit (still the French word for night) was originally venerated as the goddess Hathor or Athyr.

The Egyptians often depicted Nuit as a woman with dark skin, her body covered with stars, standing on all fours, stretching over her husband, the earth. Sometimes, like Hathor, she was also portrayed as a milk cow nursing and nourishing countless humans. The Greeks envisioned her as a woman from whom flowed a great, dark veil, often covered with stars.

The Greek Night, Nyx, is the daughter of Chaos, the goddess of darkness, the mother of dreams and death. According to Hesiod, the 8th century B.C.E. definitive writer on the Greek pantheon, Night is the Mother of all Gods, the first and oldest of all the deities, the precursor of all creation, the dark womb, if you will, out of which everything emerged.

Aristophanes (444-385 B.C.E.) agrees, saying that before there was air, heaven and earth, Night spread her black wings and placed an egg into the bosom of her husband or brother Erebus, the god whose name means ‘deep darkness or shadow’ (in the earth realm and underworld). Out of the egg hatched Love with its golden wings, and fertilized nature.

The Greeks and Romans worshiped the Goddess Night with temples, oracles, and sacrifices. What does she have in common with the Black Madonna? I think both represent a divine Dark Mother who is there to help us face that which scares us: death, dreams from the realm of the subconscious, infinite, dark space, night, etc. Like a good night’s rest, or like the dark womb, they nurture us in a mysterious darkness where they, not we are in control.

"Floating Angel" a painting by Marie LoParco reminds me of Nuit. To see more of her beautiful art on the theme of the sacred feminine visit MarieLoParco.com

The Catholic Church's Explanations for Black Madonnas

While only the Catholic Church celebrates and honors certain images with the title Black Madonna, crowns many of them, and parades them around in processions, many Catholic clerics nonetheless do not like to acknowledge that this blackness has any spiritual, much less socio-political meaning. Instead, some prefer to minimize its importance with the arguments below. The following explanations are often not wrong, but they are certainly incomplete since they don’t explain why images that were darkened by soot, fire, earth, wine baths, etc. would be honored with a special title and devotion.

1. The images were darkened by smoke from candlelight or bigger fires.

I got to see myself that there is something to this when I was in a church in Germany where many candles were burning before a Madonna icon in a nook. The white wall all around the dark icon was severely darkened from the soot. You could touch it and get your finger smeared with this sticky, somewhat oily substance.

However, the Madonna Mora of Padua is one example I have come across, where a Black Madonna was whitened using the soot excuse. They pretend that their Madonna Mora (Dark Madonna) was originally created with white skin, even though the restorers found the first layer of paint on her skin to be black!

Some people think that darkening by soot is always a lie. They ask: “If Black Madonnas turned dark from patina and soot, then why are only the faces and hands of mother and child dark, but not their clothes?” To that I say: Because they are traditionally dressed in fancy robes donated by the faithful. Many famous Black Madonnas possess the sort of wardrobe that befits a queen. The robes get cleaned, the faces and hands are left to darken. Why? Because people revered that dark skin for all the various reasons listed in this article.

Many miraculous Madonnas were offered an "eternal lamp" to burn before them, sometimes by kings and queens and such. Eternal lamps mark the holy of holies. They usually burn before the tabernacle, indicating the real presence of Christ. When they are allowed to burn before a Madonna, they mark her too as the presence of the Most High. This happened e.g. in Mende, France, Cologne, Germany, Pescasseroli, Italy, and Lord, Spain. Some Black Madonna legends even recount that perpetual lamps were found still aflame next to statues that had been hidden in the ground for centuries. (E.g. Randazzo, Sicily and Chipiona, Spain.) To any Catholic this would be a clear sign of divine presence.

Candles are people's prayers in physical form. So, the soot on Mary is all the prayers poured out on her by her children. How many times have I been in churches where dozens of candles burn before a Mary image and hardly any before Jesus. It shows where people's hearts are and where they go for help: to the Mother much more than on to the Brother.

Many Madonnas were originally darkened by candle smoke and patina, but later, during a restoration, painted black. One example is Our Black Lady of Einsiedeln. The statue was restored to her former whiteness in 1799, but it caused such an uproar in the population that the restorer had to darken her again. He attempted a compromise of dark skin but with some color in the eyes, on the cheeks and lips, but the people weren't happy until he painted the whole face pitch black. That's the spirit!

The Black Madonna of Einsiedeln, Switzerland

2. The Madonnas darkened because they were buried in the earth to save them from destruction by enemies of Catholicism, and the chemicals in the statues' paint and the earth reacted to each other. This occured during centuries of Muslim attacks, during the Wars of Religion, the French Revolution, Napoleon's conquests, and the Spanish Civil War.

I find it suspicious however, that so many statues were supposedly hidden from enemies and then forgotten. Wouldn't one generation have passed the secret of the hiding place on to the next? Maybe some of the ancient, buried statues weren't meant to portray Mary and Jesus at all. We know that quite a few Pagan statues of mother goddesses with child were Christianized and henceforth revered as Mary and Jesus, but many were destroyed by Christian zealots. So if Christians buried their statues in the ground to hide them from their enemies, why wouldn't Pagans have done the same? If some of the Black Madonnas were originally Pagan goddesses, that would explain why it took divine intervention and so many miracles to discover and rehabilitate them as Mary and Jesus.

There is another reason why Catholics bury statues: it is the proper way of discarding a consecrated object that one may want to dispose of, maybe because it has been damaged, or because it seems outdated in its style or simply not as beautiful as a newer image. It is possible that many statues were discarded when Europe switched from portraying Mary as the Seat of Wisdom to the standing Madonna.

Only, it seems that Our Mother does not appreciate being tossed out in any way, for any reason. On several occasions Our Lady has sent the message not to judge her images with ordinary eyes, but to honor them no matter how they look. In Vienna a miraculous painting by the name of Our Lady of the Bowed Head is honored in the Silbergasse. She was found in 1610, when Mary gave a Carmelite friar an irresistible urge to search a pile of garbage for something valuable until he came upon her image.[22]

Our Lady of Pompeii in her basilica is a much-loved image famous for working miracles. Yet she once was bought in a junk shop, considered very bad art and totally dilapidated.[23]

The message is clear: Honor your Heavenly Mother in all her forms and images, no matter what.

The Mother of God of Lluc, Mallorca

the Black Madonna of Cologne, Germany

3. Some statues are made of black ebony wood or other dark woods.

4. Some "Black Madonnas" were painted in the Byzantine style, which usually depicts biblical characters as dark as Palestinian Jews of that era actually would have been.

5. The medieval custom of bathing statues with wine would also have contributed to the darkening of Romanesque Madonnas. This ritual was performed once a year on Good Friday.[24]

Bathing sacred images is an ancient custom to be found in many cultures. Once a year the Romans bathed the above mentioned goddess Cybele in a river. To this day, many peoples bathe their holy images. From non-Christians in the Philippines, who bathe statues in blood,[25] to Buddhists bathing baby Buddha on his birthday in tea, to French Roma (formerly known as gypsies) who, once a year, bathe their patroness Sara Kali in the sea.

Likely, all these practices go back to the dawn of civilizations when the blood of sacrificial animals was poured over a sacred stone representing a god. Later, and particularly in Christianity, wine came to represent sanctifying blood.

6. In the Middle Ages many reputable clergymen argued that Mary obviously must have been dark skinned because that's how Luke portrayed her in all the famous icons and statues that tradition attributes to him. Some surmise that he accompanied the holy family on their flight into Egypt, during which Mary became rather sunburnt from all that riding around on donkey back, and that's how he sketched her.

7. When the Church cannot deny at all that a certain Madonna was intentionally portrayed as black, it often reasons that this was to connect her to the bride in the Song of Songs 1:5-6, who says: "I am dark and beautiful, o daughters of Jerusalem, as the tents of Kedar, as the curtains of Salma. Do not stare at me because I am black, because the sun has burned me." The website https://hermeneutics.stackexchange.com/ has a really good, detailed discussion entitled: "Black but beautiful" or "Black and beautiful" in Song of Songs? The original Hebrew word v most often means ‘and’, but depending on the context, also gets translated as ‘but’. The 2nd century BCE translation of this text into Greek in the Septuagint Bible translates the word as ‘but’.

To Jews and Christians along the centuries and millennia, the bride's blackness in the Song of Songs appears not to be something positive. She seems embarrassed by it and needs to explain it. On the other hand, she knows herself as beautiful and celebrates her blackness, comparing it to apparently significant things like the tents of Kedar, a kingdom or union of tribes, and the curtains of Salma (though nobody knows what those are anymore).

“black as the tents of Kedar”

The Bride of Christ, as seen by Michael Jeshurun

In monastic communities the bride in the Song of Songs is viewed as the bride of God, i.e. the mystic's soul that longs for intimate union with God in general, and, more specifically the Virgin Mary as the foremost soul in union with God, often called the spouse of the Holy Spirit. As Teresa of Avila says in her "Meditations on the Song of Songs" chapter 6,8: "O Blessed Lady, how perfectly we can apply to you what takes place between God and the bride according to what is said in the Song of Songs."[26]

From the point of view of art history, the Church is right in that many of the now Black Madonnas were originally white and darkened over the centuries. Even scholars who connect the phenomenon of Black Madonnas to ancient goddess cults acknowledge this. (E.g. Brigitte Romankiewicz, "Die Schwarze Madonna: Hintergruende einer Symbolgestalt" and the above cited Francois Graveline) Apparently the Madonnas darkened over time, with age, exposure, and - as the faithful say - because Mary (with Jesus) took upon herself the sin and suffering of humanity. This darkening was seen as a significant divine communication - maybe precisely because it was not something man-made.

Especially during the 14th to 17th centuries, when the plague, the Black Death, was wiping out entire populations all over Europe, people took refuge in Black Madonnas. It was reminiscent of the story in the Bible (Numbers 21:6-9) where God instructs Moses to heal those who were mortally wounded by snake bites by making them look at a bronze sculpture of a snake. Similarly, looking at a Black Madonna was hoped to protect from the Black Death. (The "principle of similarity", i.e. of using a minute amount of the pathogen as a healing remedy is still used today in inoculations and homeopathy.) Graveline explains that during that time fervent masses of faithful went on pilgrimage to the most famous Black Madonnas of Le Puy, Chartres, and Rocamadour.[27]

Seeing this, those who had less important but similar statues of the "Seat of Wisdom" in their possession, did not hesitate to paint them black, in order to draw larger crowds. This is how the Madonnas of Vauclair, Orcival, and Moulins became black.

Other Madonnas, that had already been celebrated as Black, were given a coat of black paint when they were restored in the 18th century, rather than whitening them, as is sometimes done today.

While the church puts forth some valid arguments, none of them answer these questions: Why do people insist on calling Madonnas black when they are only brown or made of wood? Why do the faithful call her black while no one mentions the blackness of Baby Jesus whom we find so often in her lap, just as dark? Why are almost no statues of Jesus or the saints celebrated as black? And why are there, if no Romanesque then certainly Baroque statues of Mary that were conceived as black from the beginning? It seems there is a need for a black Mother but not for a black baby. Why?

Christian and non-Christian Feminist Views

Many non-Christian feminist thinkers see Black Madonnas as an expression of the people's longing for their old, pre-Christian goddesses. To them the Virgin Mary is a diluted, subjugated version of the more powerful and authentic pagan goddesses. She is an illegitimate Christian graft onto pre-Christian goddesses, designed to fool goddess worshippers into believing that they could make their spiritual home in the patriarchal fold of the Catholic Church. They would urge the Virgin Mary and her devotees to purge themselves of patriarchy and to emerge as the true goddess and her worshippers which they are at heart.

Then there are Christian feminists such as Charlene Spretnak[28] and myself. We acknowledge Mary's sisterhood with the goddesses as well as the pre-Christian roots of her cult. We are also aware of the patriarchal churches' efforts to control Mary. Nonetheless we experience her as extremely powerful, and no more oppressed than Greco-Roman, Mexican, and other goddesses. Historically Christian churches have certainly done what they could to limit her influence, but they never succeeded for very long. Every wave of suppression has been followed by one of renewed enthusiasm. When people are in danger of forgetting their Mother, She has ways of reminding them! She simply sends some apparitions, makes a statue cry or ooze oil, or works a few miracles, and then there is no stopping her followers.

The Madonna in the church of the Trappist abbey for men and women in Trefontane, Rome. Notice that she holds the symbols of St. Peter’s, i.e. the Pope’s power: the keys and the bishop’s staff and the inscription says: In me is all hope.

If you doubt her power in Christian history, just see how many churches in Europe are dedicated to her! How often do you enter a church named after her to find a big statue of her in central position, while you almost have to search for any depiction of Jesus! Andrew Harvey and Eryk Hanut's book "Mary's Vineyard" is full of quotes attesting to the leading role of Mary in many Christian lives. Here is but one of Sergei Bulgakov: "The Mother of God, since she gave her son the humanity of the second Adam, is also the mother of universal humanity, the spiritual center of all creation, the heart of the world. In her, creation is completely divinized, and conceives, fosters, and bears God."[29]

Throughout the Middle Ages European Christians were deadly afraid of God and Jesus who judged and damned to eternal hell fire. Their only hope and refuge was "Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy, our life, our sweetness, and our hope!" (The beginning of a prayer at the conclusion of every Catholic mass until the "modernizations" of the 1960s.)

Is the Mother of God Christian?

In her book "Missing Mary" Charlene Spretnak suggests that the Church should not be afraid of the "pagan" roots of Mary but appreciate the added strength from deeper roots. After all the early church had no fear of using pagan temples as their foundations and hosts.[30] Perhaps it knew that the divine in its essence is neither Christian, nor pagan, nor Jewish. Jesus wasn't even Christian, but a Jew!

So is Mary Christian, or Jewish, or Pagan? Is she Catholic or Orthodox or Protestant? I don't mean images of her. I mean the real Mary who speaks to people's souls and appears all over the world throughout the centuries. The one who has been appearing in Medjugorje and said in October 1981, as civil war was on the horizon: "Tell this priest, tell everyone, that it is you who are divided on earth. (not God) The Muslims and the Orthodox, for the same reason as Catholics, are equal before my Son and me. You are all my children." (See: www.Medjugorje.org) To me, anything truly divine must transcend the boundaries of any one religion.

That brings us to the question: Is Mother Mary human or divine? Usually people say, if you think of her as divine, you are making her into a pagan goddess, but if you see her as human, then you are keeping her Christian. Personally, I don't think the matters of heaven work according to our human concepts and distinctions. I am reminded of a Buddhist story: Someone asked the Buddha: "Are you human or are you divine?" He wasn't going to apply either category to himself but answered: "I am awake!"

Many Christian theologians think of Mary as divine. Even Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) called her "divine mother" during Pope John Paul II's funeral mass. To distinguish her status from that of Jesus, it is only said that she became divine by grace, whereas Jesus was always divine by nature. I.e. she reached complete "divine" or "mystical" union. She is the prime example and personification of that which was the goal of generations of Christians: divinization. St. Thomas Aquinas explains: "The only-begotten Son of God, wanting to make us sharers in his divinity, assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods."[31]

So, according to a Catholic dogma (which admittedly is not often proclaimed), the whole purpose of Gods incarnation in Jesus is to help us overcome the division between God and humanity. But here we are, still quibbling over whether the Virgin Mary is human or divine.

I think we have a beautifully balanced story if we consider that: "God created the earthling (Hebrew: ha adam) in his image; in the divine image he created him; male and female he created them. (Genesis, 1:27) That is to say, God must have male and female aspects, i.e. opposing complementary elements. (Remember Lady Wisdom.) To teach us about the union of divine aspects God ordains the divine to become a man (Jesus) through a woman (Mary), and then for that woman to become divine. "Woman clothed in the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars." (Revelation, 12:1) Hence God became one of us, and one of us became completely one with God, because we are all called to become human and divine.

Leftist Views

These are most notably represented by Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum in her book "Black Madonnas: Feminism, Religion, and Politics in Italy"[32]. Birnbaum portrays the Black Madonna as a rebel against the establishment which says that white and male is superior to and meant to rule over black and female. Black Madonnas are a subversive expression of an unwillingness to conform to norms set by the ruling class and culture. They echo distant memories of African and European dark goddesses and also express solidarity with the darker working class.

It is true that during the European Middle Ages black was the color of the poor, of lowliness and renunciation, while the rich reveled in expensive colors.[33] Hence a black Mary may have communicated her solidarity with the poor in a visual way to the illiterate masses of medieval Europe. The educated could read about that solidarity in her famous biblical hymn, the Magnificat, where she praises God for throwing the mighty from their thrones while lifting up the lowly. (Luke 1:52-3).

Interestingly, I found confirmation of some of Birnbaum’s hypothesis in Roy A. Vargheses book "God-Sent: a History of the Accredited Apparitions of Mary". He is the picture of the sort of patriarchal thinker Birnbaum probably sees as the enemy. Yet he has a soft spot: his love of Mary. And so he tells the story of Our Appeared Lady (Nossa Senhora Aparecida), the black Madonna and patroness of Brazil.[34] She was found at a time when Brazilian slaves were demanding freedom and Princess Isabel was refusing to sign their freedom act. When the Queen of Heaven intervened by performing many miracles through a "black" statue, the earthly princess saw the light and understood the message. She signed the papers abolishing slavery and offered the black Virgin a precious crown.

Our Appeared Lady (Nossa Senhora Aparecida)

According to China Galland on the other hand (in "The Bond Between Women" 1998, p. 183-5) all the efforts of the Divine Mother in Brazil only accomplished little to end slavery, though it did ensure her a great following among the oppressed to whom she is a symbol of liberation. Galland retells a traditional story:

"One day a slave was traveling with his master near the small shrine that had been constructed for Aparecida. The man entreated his master to stop the wagons and let him pray at the door of the shrine. As soon as he knelt down in the doorway, the heavy chains he wore fell off his hands and feet, and the wide iron collar around his neck broke apart. His master declared him free: the Virgin herself seemed to command it."[35]

Galland also paraphrases Archbishop Dom Aloysius Lorscheider as explaining the Virgin's title "Mother of the Excluded of Brazil": "all who have been marginalized by conventional society are upheld and revered in the figure of this Virgin - the poor, the broken, and the dark. She is their champion. She is black because she is the Mother of All."[36] Brazilians call her Mari-ama; and ama to them is the black wet nurse who nurses black and white children without discriminating.

Brigitte Romankiewicz finds the same rebel spirit of the Virgin Mary in the recurring stories of her escaping the plans of church officials. The theme is this: a statue of Mary (often, but not always dark) is found in the wilderness under miraculous circumstances. The faithful flock there in pilgrimage without awaiting the sanction of the church. Once the clergymen grant it, they want to move her to the nearest parish church. They try to control her and to bring her home into the established fold of the church, but Mary has a mind of her own. Miraculously the statue keeps returning to its place of discovery until she gets her own sanctuary in the place of her choosing. According to legend the Virgin of Vassiviere escaped three times, the one of Neunkirch nine times, the one of Polignan in the Pyrenees several times, breaking her chains on her final escape. As you can see in the index below the table of content at the top of this page, the story of the Dark Mother asserting her power and self determination, the power to chose her home in nature and to be who she wants to be, is the most repeated leitmotif of all the recurring Black Madonna themes. The power of self determination of the sacred feminine is arguably the most important message of the Black Madonna!

In that same vein, Mary Beth Moser emphasizes the Black Madonna as a feminine spirit that will not tolerate disrespect. In her book "Honoring Darkness" she lists many incidents where people who showed disrespect to dark Mothers, were miraculously punished by Heaven.[37]

Racial Explanations

Some people regard statues of Black Madonnas not as symbolic of an abstract principle, but as literally depicting Mary as African. Their speculations as to why white Europeans would portray the mother of Jesus as a black African woman differ.

One group claims it is for the simple reason that that's what she was, a black woman. After all, we know from the Bible that there were African Jews at the time of Jesus. Acts 8:26-40 recounts how an angel sends the apostle Philip to convert a high ranking Ethiopian Jew, who had come to Jerusalem on pilgrimage. That there were intermarriages between Israelites and Ethiopians is attested by the story of Moses marrying a Cushite, i.e. a non-semitic Ethiopian woman, thereby incurring the wrath of his sister Miriam. If Israelites married Cushites, all the more can one assume that they would marry Amhara, i.e. semitic Ethiopians. Considering all the history the Israelites shared with Egypt (including the flight of the Holy Family to that land), one can assume much intermarrying between Israelites and Egyptians of all colors. The most famous example is Hagar, the Egyptian maid with whom Abraham conceived Ishmael, father of the Arabs. So Mary of Nazareth's complexion might have been many shades of brown.

As a matter of fact, the earliest extant depictions of Mary, those in the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome, dated to 170 – 250 A.D., clearly depict Mary as a Black woman three times. One may look at the first two frescos and think: “Oh well, maybe they didn’t have any lighter skin colors in their palette or they portrayed all humans in that color, or maybe the original skin color darkened over time.”

But then you look at the third fresco, the Adoration of the Magi, and you have to admit: they had other skin colors available and they very consciously picked a very dark brown for Mary and Jesus. As Paco Taylor points out in his excellent article: “Remembering When Mary Was Black: Thoughts on the Black Madonna iconography of medieval Europe” we clearly see here a depiction of three men of three different races, one white, one reddish brown, and one black.

Adoration of the Magi, 2nd-3rd Century Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, source: Web Gallery of Art

Mary is seated with the infant Jesus held to her bosom as the noble pilgrims present the gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. … The darkest of them is pictured nearest to the Madonna and Child, with the brown appearing at the center, and the white appearing third.

The fact that this is mentioned isn’t to suggest that they were originally pictured in an order that would indicate significance or importance. What is noteworthy, though, is the difference between this fresco and hundreds of later, Gothic depictions of the Annunciation. Typically, two kings, who are depicted as Europeans, are placed closest to Virgin and Child (also rendered as European). And the Ethiopian King — when he is rendered as such — is generally the one who is placed furthest away.” Here he is closest in space and in color, leaving no doubt of the artist’s intention to show that Mary and Jesus were Black!

A 15th century example of Mary portrayed as a Black woman surrounded by White men from Abuna Yemata Guh church in Ethiopia.

Others claim that Black Madonnas portray Mary and Jesus as an Africans, because all of us are originally African, because the human race as a whole was born on that continent. In "Dark Mother: African Origins and Godmothers" Lucia C. Birnbaum recounts archeological and DNA research which suggests African beginnings of humankind.[38] She argues that the mystery of Black Madonnas in European countries points to an unconscious memory of those roots. Presumably our DNA still retains an imprint of our first mother: a black woman, and our subconscious still remembers the first deity we ever worshipped: a dark Divine Mother.

Birnbaum argues that Africans migrated all over the world, implanting everywhere the worship of a Dark Mother. As proof of the African roots of a worldwide culture, she wants to trace all stone age (neolithic) uses of stone altars (dolmens) and monuments (menhirs) back to Africa. Not only that, but she also lays into the African cradle the common symbols of the Goddess: the pubic V or triangle and the color ochre red, which imitates menstrual blood. Shespeaks of the 'African origins of belief in the goddess' as if humans on all continents couldn't have felt that same impulse of venerating the Divine in motherly form. All over the world there are birds which build nests and migrate - does that mean they all originated in the same place? I think worshipping a divine mother is a basic human instinct, not limited to any particular race. It makes such immediate sense to worship her as all-inclusive, all-pervading, as light and darkness, day and night, that one shouldn't put it past any race to come up with light and dark divine images.

People who think of Black Madonnas as African mothers stress the "African features" they perceive in some of these statues. Below are two who are described as "clearly African".

Santa Maria in Portico in Campitelli Italy, 10th century, enamel

Our Lady of Nuria, Queen of the Pyrenees, Spain, 12th century

I guess our eyes see what our minds tell them to see. These ladies don't look African to me, and I don't find it a compliment to call the often rough and primitive features of some of the Romanesque sculptures "African". I admit that the Black Virgin of Chastreix and especially her son do look African to me. However, we also have to remember that in the USA we tend to imagine that all Africans share the same features we are used to seeing on African Americans, who are mostly descendants of slaves from West Africa. There are plenty of Africans in North Africa and along the Red Sea, who have rather “European” features, which is why some Black Madonnas were called “the Ethiopian” or “the Egyptian”.

Anyway, what we see in any given statue is our private matter. What is more important for this study is what the faithful masses of past centuries saw in them and what the artists' intentions were. Were European Black Madonnas intentionally portrayed and consciously seen as African? The answer is, sometimes yes. Our Lady of Meymac with her turban points to the artist's intention of making her look African, or at least "oriental", which in the Middle Ages meant anything South or South-East of Europe.

the Egyptian, the Black Virgin of Meymac, France, 12th century

That the people regarded her and some other statues as African is proven by the epithets they were given. The French Virgins of Le Puy, Chartres, Meymac, and perhaps others, were nicknamed "the Egyptian" for centuries. The Italian Virgins of Montevergine, Somma Vesuviana, and Naples are all called "Mamma Schiavone", Slave Mama.[39]

Our Lady of Le Puy (left, photo: Francis Debaisieux) and Chartres (right), France, both are reproductions, because the originals were burnt during the revolution, like witches on public execution pyres, to cries of: "Death to the Egyptian!"

Maybe God wanted to challenge racism by inspiring white artists to create black Madonnas and then by giving them special powers. For challenge S/he did. To this day the following story is told in the brochures of Tindari, the most famous Black Madonna sanctuary of Sicily, as a warning against racism.

A woman who had begged the Italian Madonna of Tindari to heal her daughter, apparently without knowing what the statue looks like. Her wish was granted and she went to Our Lady's sanctuary to thank her. Upon seeing the image, she exclaimed with racist indignation that the Madonna was an "Ethiopian" and marveled: "I traveled so far to see someone uglier than me?!" Punishment, remorse, and reconciliation were all immediate: the little girl fell from a cliff, her mother regretted her irreverence, the girl was saved by divine intervention, and the mother accepted that divine power can be channeled through black as well as white forms, all of which deserve respect.

Our Lady of Tindari, Italy, "the Ethiopian", about 7th century

Other Black Madonnas too are hailed in their sanctuaries as mothers and reconcilers of all nations and races. E.g. Our Lady of Loreto, Italy seems to enjoy a special appreciation among African Catholics, who are mentioned and welcomed with sensitivity at her Holy House. The Brazilian Aparecida's role in racial reconciliation is discussed above.

If we ask: "What was going on in Europe on the level of race relations, while the Black Madonnas were becoming famous?" the answer is, a lot. a) The Moorish occupation of Spain, Portugal, Sicily, Southern Italy, and Southern France, b) the Crusades against Muslims, and c) the discussion of the ethics of slave trade.

a) The "Moors" or "Saracens" occupied half of Spain from 710-1492, Portugal from 711 to well into the 12th century, Southern France for more than a hundred years, also beginning in the 8th century, Sicily from the 8th-12th and Southern Italy from the 8th-14th century. Who were the Moors? Good question. To the Romans they were Mauritanians who inhabited a region of modern Algeria and Morocco. To the Spaniards they were originally the mix of Arabs and Berbers (a Moroccan tribe) who conquered Spanish kingdoms. As they mixed with Spanish blood and made Spanish converts to Islam, the term came to denote any Muslim. In modern France on the other hand, it describes the inhabitants of a large Saharan area to the south of Morocco, more or less the territory of modern Mauritania. In Germany the word used to mean simply black people. This is another example of the failure of Northern Europeans to distinguish between what is Black African and what is North African, Arabic, or even Semitic. It's all foreign, "oriental", and "black" to them. (Hence, I think, the view of Isis as a "black" deity.)

b) While the people of Southern Europe dealt with Arabic and North-African Muslims in their own land, the rest of Europe did so in the "Orient" during almost four centuries of Crusades (1095 - mid 15th century). Certainly homecoming crusaders would describe to their countrymen what the Holy Land and its remaining native inhabitants looked like. They must have talked about how dark their skin was and maybe it even crossed their minds that these were the people of Jesus. (Although many preferred not to think of Jesus and the apostles as Jewish.) This may have prompted depictions of black Marys. But it still would not explain why black Jesuses were not equally as numerous or important to the people.

During the era of the crusades four little Christian kingdoms, plus scattered towns and forts were held amid the Muslim and North-African world. All of the territories shared by Christians and Muslims witnessed times of war and times of peaceful, fruitful coexistence. Europe profited immeasurably from Arabic philosophy, science, medicine, and agricultural technology. Yet most Europeans who were not used to dealing with Muslim neighbors on a daily basis, were appalled at the idea of a peaceful coexistence with the world of Islam. France was the source of much Christian aggression against the followers of Mohammed. She instigated the Crusades and her powerful Benedictine monks of Cluny turned Spanish efforts towards peaceful coexistence with the Moors into war and persecution. (see: Encyclopedia Britannica on Crusades and Spanish history)

Strange, because the same monks who publicly preached the crusades, privately engaged the Muslims in most fruitful cultural and religious exchanges. They sent their best to study at the Spanish Muslim universities of Toledo and Cordoba and translated the Coran. According to Jacque Huynen in his "l'Enigme des Vierges Noires" Benedictine monks must be credited with creating a whole new civilization by synthesizing Druidic, Christian, and Oriental culture into one cohesive system.[40] I guess knowledge is power and those monks wanted both. So they stole all the knowledge of the Orient from their Muslim brothers and then turned around and overpowered them.